In the course of your everyday work you are bound to interact with families whose beliefs or values about child rearing, communication, and everyday activities such as feeding, sleeping, toileting, discipline, and play are different from your own. It is important to recognize that these attitudes and beliefs are often bound by culture. Families, including your own, have diverse structures, living conditions, religious beliefs, socioeconomic conditions, educational levels, family values, political views and many other factors which work in combination and affect how family members respond to children.

Take a minute to think about the following scenario:

The Dilemma…

Kate, a speech therapist, has just started working with Tam and her mom Lisa. During each visit the TV plays loudly and Kate finds it difficult to observe Tam’s babbling or attempts at speech production. After a few sessions, Kate carefully asked if mom noticed a difference in her attention or speech when the TV was off, Lisa said “no” and wouldn’t turn the TV off. Instead she brought Tam’s attention to the TV and asked her what she wanted to watch. Kate quickly became frustrated because she wasn’t able to get Lisa or Tam to focus during their sessions and she didn’t want to come across as judgmental or give Lisa the message that she was being a bad parent. At the same time she was concerned that the TV was used as a babysitter and in place of opportunities for Tam to interact with mom and have rich communication experiences.

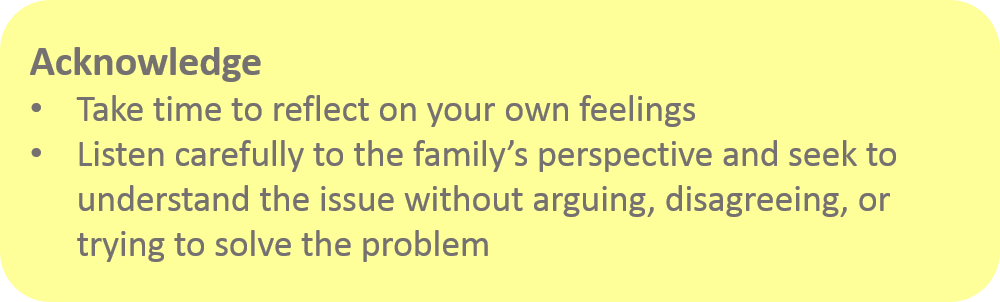

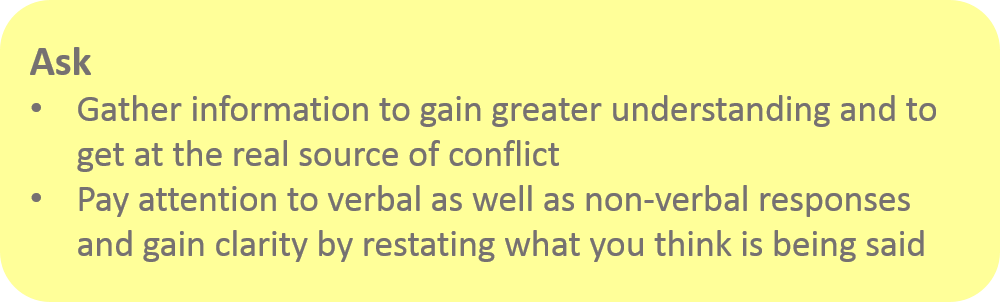

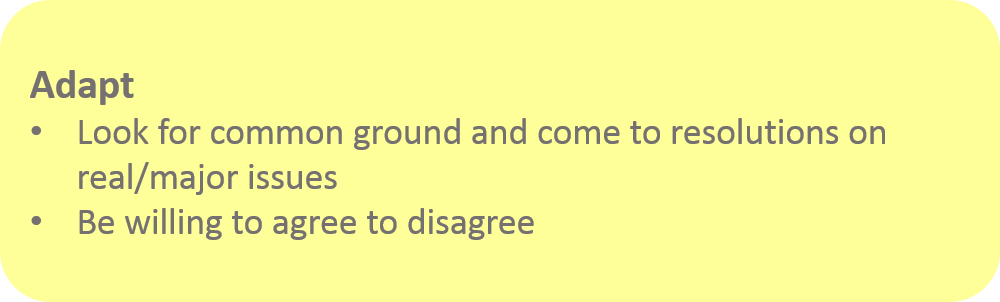

Cultural differences can play a part in potential misunderstandings and frustration. However, by acknowledging the cultural clash and engaging in discussions with the family, early intervention professionals and family members can come to a shared understanding of events as they transpire. Before you decide how to talk to a family, learn more about the tools you can use to make the process easier.

When we take the time to reflect and analyze the dilemma for underlying assumptions that are culturally based, we can begin to understand them. We can also begin to explore and imagine alternatives. Self-assessment involves examining our biases and prejudices, and developing cross-cultural skills. It helps us realize the pervasive role culture plays in our lives, become aware of our biases, and aim to change them to improve our understanding, behavior, and cultural competence.

We can take the initiative to interact, listen, and learn from people who are different in some way from ourselves. A willingness to engage in critical reflection and open communication are important to understanding and building successful partnerships with families. Although we may feel inferior or inadequate when we admit that we do not understand something about a family’s culture, it can provide an opening to inform, clarify, or elaborate on information. Honesty about what we don’t understand can result in increased understanding, rather than creating a roadblock.

Another way to learn about individuals from a different cultural or ethnic group is to focus on similarities between you and the other party, or to find common ground. This connection can revolve around occupations, personal life, hobbies or interests, common concerns, and, of course, a child. We can also make a commitment to participate in formal cultural training or development opportunities and then integrate the new information into our personal lifestyle and professional practices.

What happened next?

What happened next?

After using Acknowledge, Ask, and Adapt, Kate recognized that Lisa felt overwhelmed, and found that even when watching with Tam, using the TV gave her a much needed break, she also learned that Lisa values children’s TV programming and feels it is beneficial to her child. In addition, their discussion revealed that Lisa was raised in a similar way and from her perspective when the TV is on, the child is more content. This process also allowed Kate to express her concerns. Kate and Lisa agreed to talk about children’s programming that promotes interaction, they also discussed alternating TV time with other activities. Now when Kate arrives if the TV is on they incorporate it into the first few minutes of their session and spend the remainder of their session time interacting in other family routines.

After using Acknowledge, Ask, and Adapt, Kate recognized that Lisa felt overwhelmed, and found that even when watching with Tam, using the TV gave her a much needed break, she also learned that Lisa values children’s TV programming and feels it is beneficial to her child. In addition, their discussion revealed that Lisa was raised in a similar way and from her perspective when the TV is on, the child is more content. This process also allowed Kate to express her concerns. Kate and Lisa agreed to talk about children’s programming that promotes interaction, they also discussed alternating TV time with other activities. Now when Kate arrives if the TV is on they incorporate it into the first few minutes of their session and spend the remainder of their session time interacting in other family routines.

For families to be better served by Early Intervention, we need to be aware of and sensitive to our own beliefs and the belief systems of the families we serve in order to use empathy and respect to facilitate understanding and bridge these differences.

To learn more about the Acknowledge, Ask, Adapt process visit WestEd’s Program for Infant Toddler Care (PITC) website.